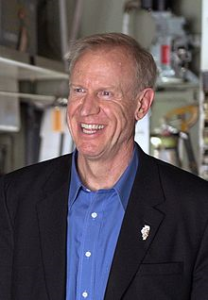

Illinois Gov. Bruce Rauner, elected in 2014 and up for re-election this year as the Republican nominee, has made manipulative politics the centerpiece of his first term, at the expense of passing a budget through a Democrat-dominated legislature. Illinois has had such split governance before, but other governors at least understood that their first responsibility was to pass a budget so the state could pay its bills, even if that required some compromise. Rauner instead has thrown down the gauntlet repeatedly, often on issues such as right-to-work legislation that were not directly related to the budget but became his bludgeons to get what he wanted. The result was a two-year stalemate that saw Illinois continue many of its programs under court mandates rather than through legislation. Finally, enough Republicans bucked their own governor last year to force the issue and approve some tax increases to begin to pay down the state’s backlog of debts to social service providers, school districts, and state universities, among others.

You might think that, by now, Illinois would have had enough of such counterproductive, divisive politics. Compromise and disagreement always have co-habited in politics, mostly by necessity. Even in the era of Donald Trump, even in a gubernatorial election year, acting like an adult should still count for something.

Instead, Rauner on Monday used his line item veto power to revise a gun law passed by the legislature to attempt to reinstate the death penalty. The gun law would establish a 72-hour “cooling-off” period following the purchase of an assault weapon. Legislators have considered several proposals in response to the recent wave of incidents of gun-related violence around the nation and in the state. Rauner also stated that he believes the 72-hour rule should apply to all gun purchases, and proposed other gun-control measures, but it is hard to take him seriously when he makes the legislation contingent on an unrelated death penalty provision. Rauner understands all too well the political divisions inherent in gun policy, having barely survived a primary challenge from St. Rep. Jeanne Ives, a right-wing Republican from Wheaton, in the conservative evangelical heart of the Chicago suburbs. It is far easier to see a streak of raw cynicism behind Rauner’s move: How desperate are gun-control advocates to get something passed? Desperate enough to split the Democratic base by supporting reinstatement of the death penalty?

It is important to understand just how cynical this is in the context of recent Illinois history. The last Republican governor, George Ryan, placed a moratorium on the death penalty in 2000 because he found himself increasingly troubled by the number of wrongful convictions in Illinois and the possibility that, in denying clemency, he could be signing the death warrant for an innocent person. In 2003, before leaving office, Ryan commuted the sentences of all death row inmates. Despite considerable criticism at the time, Ryan mounted a stout defense of his actions.

This has been no small matter in Illinois. The list of exonerations in recent decades runs on for pages. The City of Chicago has already paid out more than $100 million in reparations for wrongful convictions resulting from forced confessions, extracted through torture, by police detective Jon Burge, subsequently convicted himself in federal court for obstruction of justice and perjury. That is not even close to the end of the story; the overall total of settlements for police misconduct, according to the Better Government Association, totaled well in excess of $500 million by 2014. Thus, the move by Ryan served to open the floodgate of grievances and reservations that finally led the legislature to abolish the death penalty in 2011, signed into law by Gov. Pat Quinn.

In the meantime, Ryan himself went to federal prison on corruption charges, followed a decade later by his Democratic successor, Gov. Rod Blagojevich, who himself seemed intent on proving that one need not be an adult to hold high office. Blagojevich is still appealing a 14-year sentence and hoping for clemency from President Trump. Illinois has had a colorful, but hardly confidence-inspiring, political history.

It is thus small surprise that there is little voter sentiment for what Rauner has now suggested. The notion that it may be better to let a murder convict sit in prison, where at least he or she may still be alive if or when a wrongful conviction is overturned, seems to have become the dominant sentiment among most of the body politic. Illinois does not need to revisit that conclusion so soon after achieving this historic landmark in its long history of criminal jurisprudence. We still don’t know what other innocent persons might be sitting on death row if the state had not ended the death penalty.

Rauner is trying to parse the distinction between potential wrongful convictions and legitimately convicted murderers by limiting the application of the death penalty in his amendatory veto language to those who murder police officers or kill two or more people. Asked why his proposal should not include murder of firefighters or teachers, Rauner declared himself open to expanding the list of victims for which the new death penalty would apply.

And thus, Rauner begins the process of frog-marching Illinois back into its dark past, picking scabs and reopening old wounds from a past that most of us have already chosen to put behind us.

Rauner also introduced in his amendatory veto a new standard of “beyond all doubt” in place of “beyond all reasonable doubt” for such convictions. But in practice, how does a jury, or a judge, truly distinguish one from another? If any doubt exists about convicting a defendant in a murder trial, shouldn’t that doubt be “reasonable” before it is even considered? In light of past miscarriages of justice, who will guarantee a just result before imposing the death sentence? Rauner’s tweaking of language does almost nothing to resolve the manifold doubts that moved public opinion toward the elimination of the death penalty in the first place.

The legislature, as always, has two options. One is for enough Democrats and Republicans, bipartisanly sick of this brazen manipulation, to override the amendatory veto with a three-fifths vote in both houses. The other is to do nothing, in which case the legislation goes nowhere. Legislators are also actively pursuing other measures concerning state licensing of gun dealers. The possibility of approving Rauner’s version of the bill creating the cooling-off period is, in fact, almost nonexistent, and Rauner’s true goal may be to satisfy the Republican right wing by killing the gun-control measure that passed and blaming its failure on Democrats. If so, voters may want to consider just how cynical they want their governor to be.

Jim Schwab

Related links for this article:

“Rauner’s death penalty ploy,” Chicago Tribune editorial

“In Rauner’s gun proposal, politics ahead of policy,” Chicago Tribune column by Dahleen Glanton

“Lawmakers revise plan to license Illinois gun stores,” Chicago Tribune