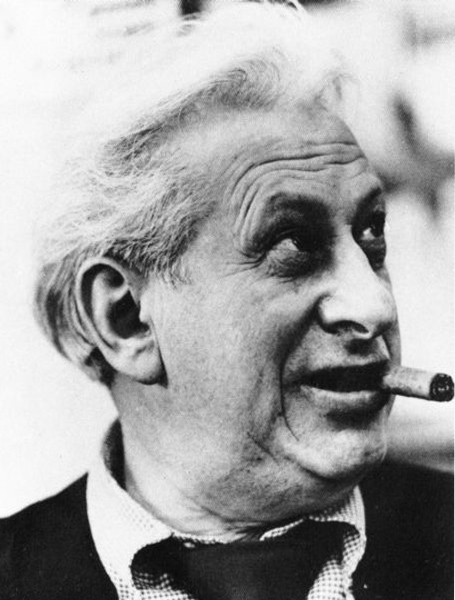

Studs Terkel, Nelson Algren, Mike Royko, and a “woman friend no one has identified.” Photo provided by Richard Bales, given to him by Algren’s first bibliographer, Ken McCollum.

I’ve been holding on to this piece for a week. It’s not that I wrote it and then sat on it, but that I am writing it now based on an A&E feature I encountered in the Chicago Tribune last Sunday. I didn’t actually finish reading the article until today. My real reason for delay is that I spent the week going to work, participating in seven job interviews for a new position at APA, trying to finish work on a manuscript, all while slipping not so quietly into a diagnosis by Friday of acute bronchitis. In short, at the end of each day I had no energy to write anything. So thank the antibiotics and the inhaler. I’m on the mend, but still less than robust and vigorous. But I can get this done.

The article, “Studs forever,” by Rick Kogan, a long-time WGN radio host and journalistic observer of the cultural scene, tells the story of a remarkable and worthy effort by a team of relatively young archivists led by Tony Macaluso at WFMT-FM, which long hosted the Studs Terkel Show, to digitize some 5,600 recorded radio shows that Studs Terkel left the Chicago History Museum after his death in 2008, at age 96, after decades on the air on WFMT-FM in Chicago. Terkel led an amazing life, leading an early television show in the 1950s, hosting his hour-long interviews on a daily basis, and producing 18 books, mostly of oral history, but also some remarkably literate commentary on music, the arts, and other topics. In 1985, he won a Pulitzer Prize for The Good War, his oral history of World War II. He was both an activist and a Renaissance man. When he wasn’t busy with all that, he appeared in the occasional movie, such as Eight Men Out, the dramatization of the 1919 Chicago Black Sox World Series scandal. Studs’s intellect covered the waterfront.

The article notes that only 400 of those hours of tapes are digitized so far. You can find them at www.studsterkel.org, and more will be coming, but additional resources are needed for such a gargantuan task. What is being saved for public consumption is a treasure trove of insights solicited by Terkel, in his unique interviewing style, from some of the leading lights of his time: Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., Bob Dylan, Jacques Cousteau, Cesar Chavez, James Baldwin, Gwendolyn Brooks, Mike Royko (one of his closest friends), Bill McKibben, and who knows how many others prominent in their day. The interviews are more than just routine; they are the probings of a very curious, passionate mind, drawing the best from his subjects. They are lively elucidations of topics that remain vital: the role of art in the modern world, civil rights, free speech, racial justice, and the environment.

I say all this because I feel I owe Studs Terkel a great deal myself. He shaped how I saw my job as a writer and interviewer—not that I ever matched his skill and prolific nature—just that I learned.

Sometime in early 1984, maybe late 1983, I’m not sure, I showed up in the office of my adviser for the Journalism master’s program at the University of Iowa, John Erickson, to discuss my master’s project. At the time, I was the only person in the entire university with the oddball aim of getting two master’s degrees simultaneously in Journalism and Urban and Regional Planning, both of which were completed in 1985. The Midwest farm credit crisis was beginning to manifest itself substantially by then, and I told Professor Erickson that I wanted to produce and publish an oral history of the farm crisis. Erickson, aware unlike me that no one in the program’s history had yet turned a master’s project into a published book, never batted an eye. He suggested some resources on oral history and interviewing techniques and encouraged me to get to work. Lacking Amazon in those days, I visited Prairie Lights Books and placed a special order for the recommended reading, which showed up about two weeks later. And I got busy.

Along the way, I discovered this trailblazer in oral history named Studs Terkel and began reading his books: Working; Hard Times; and Division Street: America. I could not put them down. They remain classics, in my opinion, part of the American literary canon. And I learned both the value of asking the right questions in an interview and the art of shaping that interview into an engaging piece of literature. Aided by that inspiration, I turned that master’s degree into a book: Raising Less Corn and More Hell: Midwestern Farmers Speak Out (University of Illinois Press). But that was not until 1988, three years after I left Iowa, after Erickson and others on the comps committee told me my first 140 pages were enough, you’re graduated, do the rest later, and after my planning background helped me turn much of the same material plus other research into a consulting study for the Iowa General Assembly. But that is another story, involving another professor, John Fuller, in the School of Urban and Regional Planning, who was then employing me as a graduate research assistant. It was also in the course of my travels in conducting dozens of interviews that I met my future wife, Jean, in Omaha.

Image from Wikimedia (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Studs_Terkel_-_1979-1.jpg) By New photo (ebay) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

That would be enough to give Studs an honored place in my memories, but after my second book (Deeper Shades of Green: The Rise of Blue Collar and Minority Environmentalism, Sierra Club Books, 1994) was released, he invited me onto his show. In view of the unquestionable prominence of so many other Studs Terkel guests, this was for me a huge honor. When someone with his track record and guest list, such as it was by 1995, brings you to his radio show, someone like me, a minor author at the time, is likely to feel this is a golden opportunity. And it was.

Studs, I learned, would not take me or my book any less seriously than any of his other guests. I was part of numerous radio and television interviews about both books, so I know how most interviewers work, and Studs was nothing like them. My book sat there alongside him, well thumbed, with post-it notes hanging from numerous pages, making clear he had read it thoroughly and knew what he wanted to ask. No one needed to give him cues; he had marked it up, backwards and forwards. I was impressed. I felt I had joined his pantheon, worthy or not. I responded in kind. I don’t know; I may have been good or I may have been mediocre. It’s twenty years ago now. But I was there.

About two years later, I began a two-year stint as the president of the Society of Midland Authors, of which Studs Terkel was long a member (as is Rick Kogan). SMA was another group that had honored him for his contributions. The radio show was ultimately not the only time I met him, but certainly the most important occasion.

So now I realize the scope of the legacy of which I became for one day an infinitesimal part, but one treated that day by Studs as just as important as every other guest, because that was his way. On the way out of the studio, he insisted on giving me an autographed copy of Race. He was as genial as they come, a great human being—with that probing mind that seemed to know no limits. This is one archive that deserves to live on.

It will take a while to complete the museum’s project, which benefited initially from a $60,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, but will probably need more before it is done. Kogan notes that you can also find videos at www.mediaburn.org.

Jim Schwab