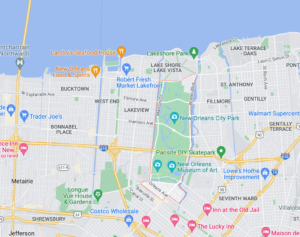

Let’s try to imagine: You are the chief executive officer for a 1,300-acre public park in New Orleans, the largest in the city, although it does not belong to the city. It is incorporated under the state of Louisiana. You spend the weekend of Friday, August 26, 2005, trying to prepare for the worst as Hurricane Katrina approaches the Gulf Coast, but you have no idea what the worst may look like. By Monday, as levees are breached and stormwater pours in from Lake Pontchartrain and the various drainage canals that perforate New Orleans, you begin to find out because 80 percent of the city is flooded, including City Park. Many areas are under eight feet of water.

Let’s try to imagine: You are the chief executive officer for a 1,300-acre public park in New Orleans, the largest in the city, although it does not belong to the city. It is incorporated under the state of Louisiana. You spend the weekend of Friday, August 26, 2005, trying to prepare for the worst as Hurricane Katrina approaches the Gulf Coast, but you have no idea what the worst may look like. By Monday, as levees are breached and stormwater pours in from Lake Pontchartrain and the various drainage canals that perforate New Orleans, you begin to find out because 80 percent of the city is flooded, including City Park. Many areas are under eight feet of water.

You are out of town because much of the city has evacuated. On Google, you cannot find out what happened to your own home because the blurry satellite images show more water than housing. If you’re in this position, so are most of your staff, many of whom no longer have homes to return to.

For many years since then, as a thought experiment in the class I teach on disaster issues for the University of Iowa’s School of Planning and Public Affairs, I have shown my own photos, taken in November 2005, of the damage in New Orleans neighborhoods, and then asked what their reaction would be if they were planners in that city and woke up to the scene I am showing them. A typical reaction is that they don’t know where to start.

Fortunately for Bob Becker, the author of New Orleans City Park: From Tragedy to Triumph, he had taken charge of City Park in July 2001, four years before Katrina struck. He had worked in New Orleans since 1971, partly with the Planning Commission, and knew his way around. He was recruited for the CEO post at City Park in part because of prior work with parks in the city. By 2005, he not only was thoroughly familiar with City Park but had engineered adoption of a master plan for the park in March of that year. He provides in his book an intriguing background history of the park, which dates to an estate settlement in the 1850s. Like many things in Louisiana, it gets complicated, but Becker focuses the vast majority of the book on his two decades of leadership at City Park, which were momentous enough, encompassing not only one of the most destructive hurricanes in U.S. history but an entire year of COVID-19 pandemic before he retired in March 2021.

Damage to Arbor Room, often used for wedding receptions, after Hurricane Katrina (all photos courtesy of Bob Becker and Pelican Publishing)

Bob Becker, a veteran planner by the time he took the helm of City Park, knew where to start after Hurricane Katrina, as daunting as the task of reconstruction may have seemed. Returning from Dallas, where he and his wife had waited out the storm at his daughter’s home, he started by trying to locate key staff members who could help with the challenges ahead. Those included everyone from plumbers and maintenance workers to department heads for payroll and human resources. City Park has always been a complex, largely self-supporting operation that has included, over time, golf courses, open space, amusements, event venues (including hosting weddings), a football stadium, and a conservatory (this does not exhaust the list), all of them deeply under water in September 2005. Becker notes that his maintenance director, Mike Mariani, called from the second floor of the Administration Building on Sunday to report that water was six inches deep and rising fast. When Becker advised him to leave but be careful, he responded that he was afraid to leave because he believed he saw an alligator swimming outside the building. It got worse from there.

Here, I must note that, in the writing, teaching, and training I have done for more than two decades on disaster recovery, I have always noted that planners in these situations must be opportunistic, adaptive, flexible, and quick to seize on serendipitous circumstances. But that does not mean unprepared; planning ahead of disasters helps create the opportunities that generate serendipitous circumstances. Good luck happens to those with good plans in place. Becker knows this as well as anyone.

It may seem a minor point to most people that the park board adopted a master plan in March 2005 after a couple of years of considering and selecting options for future development and the means for implementing them. Not only is it not minor, however, it is fundamental. In the case of City Park, the master plan became, in effect, a blueprint for recovery from massive damages and for overcoming obstacles. One offhand example Becker offers is that of the Starbucks Foundation. Several representatives showed up unannounced one day, wanting to help the city but unable to engage with anyone at the city’s recreation department. Someone referred them to City Park, where Becker was able to show them plans for shelter renovations and new play equipment. The result: a $250,000 donation from the Foundation to enable such renovations adjoining the Amusement Park. Starbucks wanted to support something tangible, and City Park had a project ready for funding.

The overall effort required more than such one-time visits, however. City Park had never had permanent fiscal support from the city where it operates, and previous attempts to enlist such support had failed. But persistent lobbying at the state level yielded the passage in 2007 of an act that created a City Park Taxing District that allowed City Park to receive both the city’s and state’s 2.5% sales tax and use tax collected within park boundaries for public works and infrastructure improvements. That added a steadying stream of revenue totaling up to $500,000 in one year. But the complete list of donations, grants, tax revenues, and operations income is impressive proof that, despite the obstacles, a public, non-profit entity can become quite entrepreneurial with the right incentives. For a special district entity like City Park, part of good planning is figuring out where the money will come from. Years later, in fact, a group of public facilities including City Park won passage of a property tax issue that redistributed existing millages to include the park. The issue on the New Orleans ballot passed with 76 percent of the vote in May 2019, providing $2 million to City Park starting in 2021 for a 20-year period. City Park finally had a truly sound base of financial support.

The overall effort required more than such one-time visits, however. City Park had never had permanent fiscal support from the city where it operates, and previous attempts to enlist such support had failed. But persistent lobbying at the state level yielded the passage in 2007 of an act that created a City Park Taxing District that allowed City Park to receive both the city’s and state’s 2.5% sales tax and use tax collected within park boundaries for public works and infrastructure improvements. That added a steadying stream of revenue totaling up to $500,000 in one year. But the complete list of donations, grants, tax revenues, and operations income is impressive proof that, despite the obstacles, a public, non-profit entity can become quite entrepreneurial with the right incentives. For a special district entity like City Park, part of good planning is figuring out where the money will come from. Years later, in fact, a group of public facilities including City Park won passage of a property tax issue that redistributed existing millages to include the park. The issue on the New Orleans ballot passed with 76 percent of the vote in May 2019, providing $2 million to City Park starting in 2021 for a 20-year period. City Park finally had a truly sound base of financial support.

Not all was smooth sailing, however. Becker details the challenges of post-disaster recovery including what one chapter labels the “silver handcuffs” of Federal Emergency Management Agency audits and the “claw-back” provisions of such audits when certain expenses are determined to be invalid or unauthorized, some of which may actually have been agreed to by FEMA personnel aware of post-disaster circumstances that may have necessitated certain decisions at the time they were made. It is an old story with which countless local officials elsewhere are all too familiar, and claims may wait years to be resolved. Becker also recounts a massive and highly publicized fiasco in which sites inside the park were proposed for trailer housing for displaced residents, only to be derailed by public opposition from nearby neighborhoods worried about who would live there, resulting in the city and City Park withdrawing their offers to host such temporary housing. The winding road to recovery is full of unforeseen snafus.

For all that, Becker’s beautifully illustrated book contains some urgent lessons for those managing communities or public facilities that may find themselves in harm’s way. His final chapter sums up those lessons, as he sees them, including not only the importance of having a plan, but having one before disaster strikes. His four paragraphs on that latter point read like music to my ears, a new setting for lyrics I had first sung as long ago as 1998. He goes on to explain why plans need an overarching goal and strategy, why it matters to plan for the unexpected, why it is difficult for a public agency to be entrepreneurial, especially in a crisis, and the importance of building an endowment to weather rainy days, literal or otherwise. His lessons alone are worthwhile reading for anyone interested or involved in public planning, especially where major natural disasters are to be expected.

Jim Schwab